Archaeologia Lituana ISSN 1392-6748 eISSN 2538-8738

2025, vol. 26, pp. 246–261 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15388/ArchLit.2025.26.10

Yevheniia Yanish

I. I. Schmalhausen Institute of Zoology, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine,

Kyiv, Vul. B. Khmelnytskogo 15, 01030 Kyiv, Ukraine

E-mail: yanish@izan.kiev.ua

Dario Piombino-Mascali

Department of Cultural Heritage, University of Salento,

Via D. Birago 64, 73100 Lecce, Italy;

Institute of Biomedical Sciences, Vilnius University,

M. K. Čiurlionio 21, 03101 Vilnius, Lithuania

E-mail: dario.piombino@mf.vu.lt

ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8277-8745

Wilfried Rosendahl

Reiss-Engelhorn-Museen,

Zeughaus C5, 68159 Mannheim, Germany

E-mail: wilfried.rosendahl@mannheim.de

Shidong Chen

Institute of Chemistry, University of Tartu,

Ravila 14a, 50411 Tartu, Estonia

E-mail: shidong.chen@ut.ee

Ester Oras

Institute of Chemistry, University of Tartu,

Ravila 14a, 50411 Tartu, Estonia;

Institute of History and Archaeology, University of Tartu, Jakobi 2, 51014, Tartu, Estonia;

Swedish Collegium for Advanced Study (SCAS), Linneanum, Villavägen 6c, 752 36 Uppsala, Sweden

E-mail: ester.oras@ut.ee

ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7212-629X

Mykola Tarasenko

Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern

Studies, University of Oxford,

1 Pusey Ln, OX1 2LE Oxford, United Kingdom;

A. Yu. Krymskyi Institute of Oriental Studies, National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine,

M. Hrushevskoho 4, 01001 Kyiv, Ukraine

E-mail: mykola.tarasenko@ames.ox.ac.uk

ORCID ID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6779-2258

Abstract. This study presents the first examination of an Egyptian mummified crocodile from the collection of the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra National Preserve (Ukraine). Archival research established that the specimen was donated to the Archaeological Museum at St. Volodymyr’s University in 1860 by Dr. Joseph Shkuratovsky who likely obtained it in Upper Egypt in the mid-19th century. The mummy had never been studied by Egyptologists, bio-archaeologists, or zoologists. Radiocarbon dating and chemical analysis of embalming substances were conducted using standard protocols. The radiocarbon results suggest a Ptolemaic Period origin (332–30 BC), although possible reservoir effects may have influenced the date. Beyond presenting this unique find to a wider audience, a key objective was to explore possible morphological criteria for distinguishing the Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus) from the West African crocodile (Crocodylus suchus), both sympatric species present in ancient Egypt. Drawing on Etienne Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire’s early observations and subsequent morphometric data, the structure of the external mandibular fenestra in this specimen was examined and compared to other examples, both modern and archaeological. The fenestra of the examined specimen exhibits features more typical of C. suchus. However, it is of importance to note that crocodile mummies cannot be assumed to represent C. suchus without a robust series of genetically confirmed specimens. Thus, the present observations are preliminary and should be regarded as a working hypothesis to be tested against other larger, well-documented datasets and utilizing DNA analyses. Morphological examination also revealed evidence that the crocodile was intentionally killed – likely by a single, precise stab wound to the neck – and that the injury was carefully concealed, suggesting a broader and more deliberate practice of sacrificial killing than previously recognized. This study contributes new archaeological, historical, and morphological data to the growing body of research on animal mummification in ancient Egypt, while underscoring the need for further work on species identification criteria.

Keywords: crocodile mummy, Egypt, Ptolemaic Period, species identification, morphometry, embalming practices.

Anotacija. Šiame straipsnyje pateikiamas pirmasis Egipto mumifikuoto krokodilo iš Kijevo Pečorų lauros nacionalinio draustinio (Ukraina) kolekcijos tyrimas. Archyvinių tyrimų metu nustatyta, kad šis eksponatas 1860 m. buvo padovanotas Šv. Volodymyro universiteto Archeologijos muziejui dr. Josifo Škuratovskio, kuris jį greičiausiai įsigijo Aukštutiniame Egipte XIX a. viduryje. Mumija niekada nebuvo tirta egiptologų, bioarcheologų ar zoologų. Datavimas radiokarbonu ir balzamavimo medžiagų cheminė analizė buvo atlikti pagal standartinius protokolus. Radiokarboninių tyrimų rezultatai rodo, kad radinys yra iš Ptolemajų laikotarpio (332–30 m. pr. Kr.), nors galimas rezervuaro efektas galėjo turėti įtakos datavimui. Be šio unikalaus radinio pristatymo platesnei auditorijai, pagrindinis tikslas buvo ištirti galimus morfologinius kriterijus, pagal kuriuos galima atskirti Nilo krokodilą (Crocodylus niloticus) nuo Vakarų Afrikos krokodilo (Crocodylus suchus) – abi šios rūšys buvo paplitusios senovės Egipte. Remiantis Etienne’o Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire’o ankstesniais pastebėjimais ir vėlesniais morfometriniais duomenimis, buvo ištirta šio egzemplioriaus išorinio apatinio žandikaulio langelio struktūra ir palyginta su kitais šiuolaikiniais ir archeologiniais pavyzdžiais. Tiriamo egzemplioriaus žandikaulio langelis pasižymi bruožais, kurie yra būdingesni C. suchus. Tačiau svarbu pažymėti, kad krokodilų mumijos negali būti laikomos C. suchus be tvirtų genetiniu būdu patvirtintų įrodymų. Taigi pateikiami pastebėjimai yra preliminarūs ir turėtų būti laikomi darbo hipoteze, kurią reikia patikrinti, palyginant su kitais didesniais, gerai dokumentuotais duomenų rinkiniais ir naudojant DNR analizę. Morfologinis tyrimas taip pat atskleidė įrodymų, kad krokodilas buvo nužudytas tyčia – greičiausiai vienu tiksliu dūriu į kaklą – ir kad sužalojimas buvo kruopščiai paslėptas, o tai rodo, kad žudymo aukojimui praktika buvo platesnė ir labiau apgalvota nei anksčiau manyta. Šis tyrimas papildo augantį senovės Egipto gyvūnų mumifikavimo tyrimų skaičių naujais archeologiniais, istoriniais ir morfologiniais duomenimis, kartu pabrėždamas būtinybę toliau dirbti su rūšių identifikavimo kriterijais.

Reikšminiai žodžiai: krokodilo mumija, Egiptas, Ptolemajų laikotarpis, rūšies identifikavimas, morfometrija, balzamavimo praktikos.

_________

Received: 25/09/2025. Accepted: 29/10/2025

Copyright © 2025 Yevheniia Yanish, Dario Piombino-Mascali, Wilfried Rosendahl, Shidong Chen, Ester Oras, Mykola Tarasenko. Published by Vilnius University Press. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Museums in Ukraine hold mummified animal remains originating from ancient Egypt’s Late to Ptolemaic Periods. These include four crocodile mummies housed in institutions such as the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra National Preserve (NPKPL), the Odessa Archaeological Museum of the NAS of Ukraine (OAM), and the D.I. Yavornytsky National Historical Museum of Dnipro (DYDHM) (Fomenko and Shamray, 2006). Additionally, two snakes (OAM) and a cat (Lviv Museum of the History of Religion) are part of these collections (Tarasenko, 2021).

Until recently, no detailed bio-archaeological or zoological study had been conducted on these mummies. The present study investigated the largest available crocodile mummy as part of the international “Ukrainian Mummy Project” (UMP). This specimen is stored in the NPKPL collections in Kyiv (Inv. No. KPL Arh-826) (Fig. 1), which presents challenges for research access due to administrative separations between the Kyiv Pechersk Lavra and academic institutions.

Fig. 1. Geographic location of Kyiv, Ukraine, where the examined ancient Egyptian crocodile mummy (Inv. No. KPL Arh-826) is preserved in the collections of the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra National Preserve.

1 pav. Kijevo Ukrainos teritorijoje geografinė vieta, kur tirta senovės Egipto krokodilo mumija (Inv. Nr. KPL Arh-826) saugoma Kijevo Pečorų lauros nacionalinio draustinio kolekcijose.

The object originates from the former Archaeological Museum at St. Volodymyr’s University of Kyiv, founded in 1836. The museum curated two anthropomorphic female coffins: one contained a Late Period human mummy (Inv. No. 1207, Khonsuirdies), and the other (Inv. No. 6499, Nesmut) came from the “second cache at Deir el-Bahari” (Bab el-Gusus). This second coffin was gifted to Kyiv by the Khedive of Egypt in 1893 (Turayev, 1899). Both coffins are now part of the OAM collection (Inv. Nos. 71700 and 71695) (Tarasenko, 2019), alongside 16 shabtis, amulets, small sculptures, and a crocodile mummy (Inv. No. 1208).

According to the museum inventory (the National Museum of History of Ukraine), this mummy and the Late Period coffin were donated to the University Archaeological Museum on May 19, 1860, by Dr. Joseph Shkuratovsky, a participant in expeditions to Egypt led by the Polish collector Alexander Branicki (Gałczyńska, 2015). Shkuratovsky likely brought these items from Upper Egypt (possibly Luxor) in the mid-19th century. Before World War II, the mummy was exhibited at the T. H. Shevchenko Central Historical Museum of Ukraine. Later, it was transferred to the NPKPL and displayed at the Museum of Atheism until 1991. Despite its public display, it had never been studied by Egyptologists, bio-archaeologists, or zoologists. On International Museum Day 2017, all Egyptian objects from NPKPL were publicly exhibited for one day before being returned to storage.

The present study builds on previous and recent research into Egyptian crocodile mummification (Nicolotti and Robert, 1994; Anderson and Antoine, 2019; Berruyer et al., 2020; Piombino-Mascali et al., 2023; McKnight et al., 2024) by providing the first detailed examination of the Kyiv specimen. This work expands current knowledge of the Ukrainian collections and situates the crocodile within the broader context of ancient Egyptian animal mummification practices. Future investigations, including computed tomography, DNA, and isotope analyses, are planned to complement the results presented here.

A critical aspect of this research is the species identification of mummified crocodiles. Genetic studies have revealed that what was traditionally considered the Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus Laurenti, 1768) is actually a species complex (Schmitz et al., 2003; Hekkala et al., 2010, 2011; Oaks, 2011; Nestler, 2012; Shirley et al., 2015; Cunningham et al., 2016). Most genetically tested ancient Egyptian crocodile mummies and some modern specimens previously identified as Nile crocodiles are now recognized as the West African or desert crocodile (Crocodylus suchus Geoffroy, 1807), originally described by Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire (1807) and long considered a Nile crocodile subspecies. However, recent mitogenomic analyses of hatchling specimens from museum collections indicate that some mummified crocodiles may indeed be true Nile crocodiles (C. niloticus) (Hekkala et al., 2022), highlighting the need for careful genetic authentication in archaeological research.

Ancient Egyptians may have recognized these differences themselves; Herodotus described two crocodile types distinguished by their aggression (Herodotus [II, 68–70] cited in Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, 1807). Today, C. suchus and C. niloticus are regarded as separate species, with overlapping geographic ranges, a phenomenon known as sympatry (Ernst, 1947).

The main goals of this study are to document and analyze the ancient Egyptian crocodile mummy in order to clarify its zoological identification, chronology, and mummification treatment. Specifically, the research seeks to conduct detailed morphometric measurements of the specimen to assess its physical characteristics and evaluate its overall preservation state, to determine its chronological placement through radiocarbon dating, and to analyze the embalming materials to identify the substances and techniques used in its preparation. Furthermore, the study compares morphological features – particularly the external mandibular fenestra – with modern and ancient crocodilian specimens to infer taxonomic affiliation. Finally, it evaluates evidence of deliberate killing and discusses the broader implications of this practice within the context of ancient Egyptian ritual behavior and the cult of Sobek. In view of the limited dataset, the taxonomic conclusions discussed herein are approached with caution and in anticipation of further investigations to confirm the hypothesized species-level distinctions.

The mummified crocodile, catalogued as a ‘Nile crocodile’ in the museum collection, was macroscopically examined. Measurements of the head and body were taken using a steel caliper with 0.1 mm precision and a tape measure with 1 mm precision. Each measurement was taken three times, and the average values and standard deviations were calculated. While a more comprehensive set of measurements was planned, the ongoing war in Ukraine prevented further data collection; therefore, the authors considered it prudent to publish the current dataset given the uncertain timeline for future analysis.

Fig. 2. Head of the mummified crocodile, dorsal view. Photo by Y. Yanish.

2 pav. Mumifikuoto krokodilo galva, vaizdas iš viršaus. Y. Yanish nuotrauka.

Fig. 3. Hindlimb of the mummified crocodile, general view. Photo by Y. Yanish.

3 pav. Mumifikuoto krokodilo užpakalinė koja, bendras vaizdas. Y. Yanish nuotrauka.

Fig. 4. Remains of a bandage on the ventral side of the mummy: a – bandage fragment; b – incision line on the ventral side of the crocodile. Photo by Y. Yanish.

4 pav. Mumijos pilvo pusėje likę tvarsčio likučiai: a – tvarsčio fragmentas; b – pjūvio linija krokodilo pilvo pusėje. Y. Yanish nuotrauka.

Measurement methods for crocodile skulls were based on established protocols (Hutton, 1987; Wu et al., 2006; Warner et al., 2016), including that of Verdade (1997). The head of the mummy is shown in Figure 2. Limb measurements (Fig. 3) and neck scale measurements were adapted by the authors. The only prior measurement recorded, dating back to 1836, was the mummy’s total length.

Typically, mummies are tightly wrapped in bandages, rendering direct visual examination impossible and necessitating non-invasive techniques. However, this crocodile mummy retained only minimal bandage fragments, allowing direct morphometric and visual examination of the specimen (Fig. 4).

The following measurements were taken:

• TTL: Total length of the body (cm)

• TL: Total length of neck scales (mm)

• DCL: Dorsal cranial length, from the anterior tip of the snout to the posterior surface of the occipital condyle (mm)

• CW: Cranial width, distance between the lateral surfaces of the mandibular condyles of the quadrates (mm)

• OL: Maximum orbital length (mm)

• OW: Maximum orbital width (mm)

• IOW: Minimum interorbital width (mm)

• WN: Maximum width of the external nares (mm)

• PXS: Length of the palatal premaxillary symphysis (mm)

• ML: Mandible length (mm)

• LM: Length of the lower ramus (mm)

• WPS: Premaxillary symphysis width (mm)

• Wmin: Minimum width of the snout (behind the premaxillary symphysis) (mm)

• Wmax: Maximum width of the neck scales (mm)

• Lmax: For the skull, the length from the end of the snout to the edge of the quadratojugal; for bones and scales, the maximum length of an individual bone or scale (mm)

Additionally, measurements were taken of both the forelimbs (manus) and hindlimbs (pes). For the manus, the distance from the shoulder joint to the elbow (humerus) was denoted as ‘H’, and from the elbow joint to the metacarpus (radius) as ‘R’. For the pes, the distance from the hip joint to the knee (femur) was designated as ‘F’, and from the knee to the metatarsus (tibia) as ‘T’. Because the measurements taken included the skin, a small margin of error may exist, but these data provide valuable insights into limb proportions.

Visual examination of the mummy was performed to identify external damage (Fig. 5), followed by trace analysis to reconstruct the method used to kill the crocodile.

Fig. 5. Disguised wound from a piercing-cutting weapon on the mummy’s neck. Photo by Y. Yanish.

5 pav. Paslėpta duriamojo-pjaunamojo ginklo mumijos kakle padaryta žaizda. Y. Yanish nuotrauka.

To analyze jaw fenestra structure, nine specimens classified as Nile crocodiles were studied, including skulls and taxidermized animals from several Ukrainian institutions (National Museum of Natural History of NAS Ukraine; Zoological Museum of T. Shevchenko National University of Kyiv; O.O. Salgansky Museum of Forest Animals and Birds; and private collections). Given recent taxonomic revisions, some specimens may not be Nile crocodiles. Publicly available photographs of crocodile skulls from various species supplemented this material.

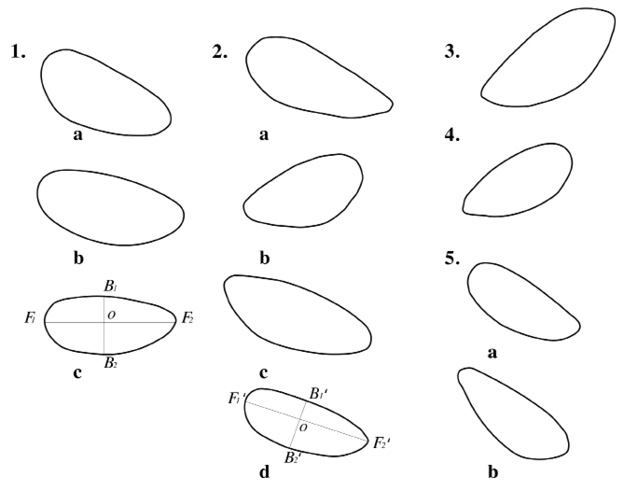

The ratio of length/width and the sharpness/roundness of the fenestrae were used to compare fenestra shapes. Figure 6 illustrates typical fenestra morphologies across crocodile species (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6. Structure of the external mandibular fenestra in crocodile species. 1 – Fenestra in the investigated mummy: (a) Porcier et al., 2019; (b) specimen from the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra National Preserve; (c) CT scan of a mummified crocodile from UC Berkeley’s Phoebe Hearst Museum of Anthropology (Dr. Rebecca Fahrig, 2010). 2a–d – Outer fenestrae in lower jaws of Nile crocodiles (museum skulls, online photographs, and CT reconstructions; Dr. John Hutchinson, 2010). 3 – Mandible of a dwarf crocodile. 4 – West African slender-snouted crocodile. 5a, b – External mandibular fenestra in saltwater crocodiles, showing shape inversion.

Arrow (→) indicates direction toward the snout of the mummy.

6 pav. Krokodilo rūšių išorinio apatinio žandikaulio langelio struktūra. 1 – tiriamos mumijos žandikaulio langelis: (a) Porcier et al., 2019; (b) eksponatas iš Kijevo Pečorų lauros nacionalinio draustinio; (c) mumifikuoto krokodilo kompiuterinė tomografija iš Kalifornijos universiteto Berklio Phoebe Hearst antropologijos muziejaus (dr. Rebecca Fahrig, 2010). 2 a–d – langeliai Nilo krokodilų apatiniuose žandikauliuose (muziejaus kaukolės, internetinės nuotraukos ir kompiuterinės tomografijos rekonstrukcijos; dr. John Hutchinson, 2010). 3 – nykštukinio krokodilo apatinis žandikaulis. 4 – Vakarų Afrikos plonasnukis krokodilas. 5 a, b – išoriniai jūrinių krokodilų apatinio žandikaulio langeliai, rodantys formos inversiją. Rodyklė (→) nurodo kryptį link mumijos snukio.

A novel graphical method, based on ellipse geometry, was developed to describe fenestra shape and distinguish the West African crocodile (Crocodylus suchus) from other Crocodylidae, Gavialidae, and Alligatoridae species. Species analyzed included those native to Africa – the West African crocodile, the Nile crocodile, the dwarf crocodile (Osteolaemus tetraspis Cope, 1861), the West African slender-snouted crocodile (Mecistops cataphractus Cuvier, 1825), and the saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus Schneider, 1801). For comparison, Gharials (Gavialis gangeticus Gmelin, 1789) and American alligators (Alligator mississippiensis Daudin, 1802) were examined.

The fenestra shape, close to an ellipse, was characterized using its major and minor axes. The major axis is the longest diameter (e.g., Fig. 6, 1c: line F1–F2), and the minor axis is perpendicular to it through the center (point O). The ratio of the minor semi-axes (O-B2 to B1-O) was calculated; values closer to 1.0 indicate a more elliptical shape. This ratio helped determine species affiliation, with the specimen most likely belonging to the West African crocodile rather than the Nile crocodile.

Measurements were conducted using millimeters or pixels (for photographs). Because the ratio of semi-axes is scale-invariant, it remains constant across magnifications and photo sizes. For mummies and modern specimens, fenestrae were measured using Paint 3D software (Supporting Figs. S1 and S2). To verify consistency, measurements were repeated at different magnifications with a caliper, producing comparable preliminary results.

A minimally invasive sample of integument and underlying soft tissue was taken for radiocarbon dating (Rosendahl and Döppes, 2015). The sample was analyzed by the Curt-Engelhorn Centre of Archaeometry, Reiss-Engelhorn Museums, Mannheim, Germany. It was washed with benzene to remove potential bitumen-based embalming contaminants. Details of the sample pre-treatment, graphitization, and AMS measurement (MICADAS system) are described by Kromer et al. (2013). The conventional radiocarbon age (14C age) is expressed as years Before Present (BP; with ‘Present’ referring to 1950), including standard deviation (±). Calibration into calendar years was performed using SwissCal software (L. Wacker, ETH-Zürich) and the INTCAL20 calibration curve (Reimer et al., 2020) (Table 1).

Fig. 7. Side view of the crocodile mummy’s head showing the external mandibular fenestra. Photo by Y. Yanish.

7 pav. Krokodilo šoninis vaizdas. Y. Yanish nuotrauka.

Table 1. Results of the archaeometric analysis

1 lentelė. Archeometrinės analizės rezultatai

|

Sample |

Provenience |

Lab. No. |

Material |

14C age (BP) |

δ13C (‰; isotope determination from the AMS system) |

Quality measures |

Cal. 1σ |

Cal. 2σ |

|

Crocodile mummy |

Ancient Egypt |

MAMS 50847 |

Biological (non-bony tissue sample) |

2124±21 |

-17.7 |

C:N = 3.2 C% = 42.5 Collagen yield 1.7% |

cal. BC 173-60 |

cal. BC 339-54 |

For embalming material analysis, 10.1 mg of residue from the mummy’s skin surface was sampled. Extraction and analysis were conducted at the Archemy Laboratory, University of Tartu, Estonia. Solvent extraction followed established protocols (Evershed et al., 1990; Oras et al., 2020). The sample was sonicated in dichloromethane (DCM) and methanol (MeOH) (2:1 v/v) for 15 minutes, centrifuged, and the lipid fraction was collected. This process was repeated twice. The lipid extract was concentrated under nitrogen, derivatized with N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetamide (BSTFA) containing 1% TMCS at 70°C for one hour. The sample was redissolved in 0.1 mL of DCM and transferred to an auto-sampling vial containing 10 μL of C36 alkane internal standard (1 μg/mL). The sample was then analyzed via GC–MS using an Agilent 7890A gas chromatograph equipped with an Agilent Silica Fuse DB5-MS column (5%-phenyl-methylpolysiloxane, 30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm) and connected to a 5975C mass selective detector. One microliter of the sample was injected through the splitless inlet at 300°C, with helium as the carrier gas at a constant flow rate of 3 mL/minute. The GC column was held at 50°C for 2 minutes, then ramped to 325°C at 10°C/minute and maintained for 15 minutes, while the mass spectrometer scanned ions from m/z 50 to 800 with an ionization energy of 70 eV. Chromatographic and mass spectral data were interpreted using NIST library matches via Agilent ChemStation software.

Radiocarbon dating of the biological sample yielded an age of 2124±21 years BP, which calibrates to 173–60 BC (68% probability) and 339–54 BC (95% probability) for the specimen (Lab No. MAMS 50847). First, potential contamination from embalming resin cannot be entirely excluded despite the sample preparation protocols, although its influence is likely minimal. Second, and most importantly, because West African crocodiles inhabit both freshwater and brackish environments and feed partly on aquatic resources, the results may be influenced by the reservoir offset (RO), potentially affecting the dating accuracy (Lanting and van der Plicht, 1998; Keaveney and Reimer, 2012). Based on the species’ known life history, the actual dates are likely younger than these estimates. Unfortunately, without paired terrestrial samples (e.g., textiles) or local RO correction, the margin of error cannot be reliably assessed. Dating the textiles is also challenging due to their potential reuse in mummification (Richardin et al., 2017). Nevertheless, previous studies on sacred ibis, which similarly feed partly on aquatic sources, indicate that RO may not substantially affect dating (Wasef et al., 2015). The crocodile mummy in this study likely dates to the Ptolemaic Period (332–30 BC), coinciding with the height of the cult of Sobek in Kom-Ombo (Hopfner, 1913; Bresciani, 2005; Ikram, 2010), although somewhat later dates remain possible. This preliminary result aligns with previous analyses (Richardin et al., 2017) and suggests that reptiles were used for mummification from the Late Period through the Ptolemaic and Roman eras.

GC-MS analysis revealed that embalming resins consisted primarily of plant oils and resins. The palmitic-to-stearic acid ratio (C16:0/C18:0) of 2.7 indicates a significant presence of plant oil (Evershed et al., 2002), supported by the abundance of unsaturated fatty acids such as octadecenoic acid (C18:1). The detection of long-chain fatty acids (C23:0 and C24:0) along with sugars including levoglucosan and pyranose suggests the presence of plant gums (Buckley et al., 2004). Aromatic compounds like benzoic and hydrocinnamic acids, common in various plants (Tchapla et al., 2004), were also identified. Furthermore, phenolic compounds, phenanthrene derivatives, and diterpenoids of the abietic acid family point to the use of Pinaceae resins and tars (Evershed et al., 1985; Oras et al., 2020). Cholesterol and its derivatives were detected, which could originate from either the embalming substances or the crocodile tissue (Ménager et al., 2014).

Morphologically, the crocodile’s total length was measured at 165.0 cm, which is slightly longer than the previously recorded 161 cm at the time of museum acquisition (Table 2). The mummy appeared to have been opened along the ventral side and possibly eviscerated (Fig. 4). Damage to the right side, likely sustained during storage or transport, revealed no internal organs in the thoracic and upper abdominal cavities, although organs may remain in the lower abdomen – which is a question that could be clarified by utilizing computed tomography.

Table 2. Results of the morphometric study of the crocodile mummy

2 lentelė. Krokodilo mumijos morfometrinio tyrimo rezultatai

|

Cranium, mm Lav±σ |

Body, mm Lav±σ |

Neck scales, mm Lav±σ |

R, mm Lav±σ |

H, mm Lav±σ |

F, mm Lav±σ |

T, mm Lav±σ |

|

|

TTL |

1650.0±1.04 |

||||||

|

TL |

260.0±0.2 |

||||||

|

DCL |

255.1±0.1 |

||||||

|

CW |

125.3±0.1 |

||||||

|

OL |

38.1±0.1 |

||||||

|

OW |

28.1±0.1 |

||||||

|

IOW |

22.2±0.1 |

||||||

|

ML |

300.5±0.2 |

||||||

|

PXS |

62.2±0.1 |

||||||

|

WN |

21.3±0.1 |

||||||

|

WPS |

46.1±0.1 |

||||||

|

Wmin |

42.0±0.1 |

||||||

|

Wmax |

16.4±0.1 |

||||||

|

Lmax |

310.2±0.2 |

72.2±0.1 |

113.3±0.1 |

123.1±0.1 |

113.0±0.1 |

Species identification based on morphology remains challenging. Although Saint-Hilaire (1807) distinguished Nile and West African crocodiles by differences in the number and structure of nuchal scutes and skull proportions, part of the neck on this specimen’s right side is missing (Figs. 2, 7), thus limiting assessment of scute features. Four preserved plaques in two rows of a similar size resemble the West African crocodile’s pattern, but poor preservation precludes definitive identification based on this characteristic alone.

The skull’s proportions further support the West African crocodile hypothesis: the ratio of the greatest lateral skull length to the greatest posterior breadth (Lmax/CW) is 2.47, which is consistent with previously published data for that species. This ratio tends to decrease with an increasing body size (De Cupere et al., 2023), and because the specimen is relatively small (165 cm), the observed value aligns with expectations. Therefore, with moderate confidence, the specimen likely represents a West African crocodile.

In contrast, based on the findings of De Cupere et al. (2023), the shape of the external mandibular fenestra in the lower jaw could potentially differentiate between species such as the Nile crocodile and the West African crocodile. However, because the skull of the specimen in the De Cupere’s study was not preserved, direct comparison with the present specimen is not possible. To explore this, fenestra shapes from photographs of three crocodile mummies (including the Kyiv Pechersk Lavra specimen) and modern crocodiles of various species were measured. The ratio of semi-minor axes (O-B2 to B1-O) was calculated repeatedly with minimal measurement error. The Kyiv Pechersk Lavra mummy’s fenestra ratio was 1.3±0.01, compared to 1.2±0.1 and 2.0±0.1 for other mummies, while modern species showed ratios ranging from 1.4 to 1.8, except the West African crocodile which exhibited a less pointed fenestra shape. Although these observations hint at possible species-specific fenestra morphology, the extremely limited sample size, lack of genetically confirmed specimens, and absence of comprehensive comparative datasets prevent definitive conclusions. As a preliminary pilot study, these data instead emphasize the need for further investigation involving larger series of well-identified modern specimens, including CT imaging.

During examination, a 25.0 mm by 9.5 mm hole was found on the dorsal neck region, consistent with a stab wound inflicted by a long dagger (Fig. 5). This injury was carefully concealed with a soil-like substance that sealed the wound, possibly a resinous material, although no chemical analysis of this substance was performed.

The cult of the crocodile (msḥ) was widespread across ancient Egypt. It was closely linked with the worship of the god Sobek, who was revered in the crocodilian form (Hopfner, 1913; Brunner-Traut, 1980; Kockelmann, 2017). Like snakes, crocodiles held an ambivalent symbolic role: they were both objects of reverence and feared creatures. Crocodiles were honored in many Egyptian localities – including in the Fayum region, the Delta, and Upper Egypt (Kákosy, 1980) – and yet in other areas such as Elephantine, they were considered dangerous pests and exterminated. Protective texts such as the Book of the Dead illustrate this duality, portraying crocodiles as threats to the deceased and showing their defeat by human agents (Frankfurter, 1998; Quirke, 2013).

The specimen studied here represents a young crocodile, based on its total length, which was insufficient for sexual maturity. Whether it was captive-bred or wild-caught remains unknown. Prior research (Porcier et al., 2019) has established that crocodiles were often deliberately killed for mummification, supporting the interpretation that the examined crocodile from the Kyiv Pechersk Lavra was similarly sacrificed. The injury identified – a clean, angled stabbing wound likely severing the underlying cervical vertebrae – would have been fatal, consistent with a controlled killing rather than accidental death.

Given the difficulty of precisely stabbing a struggling crocodile, it is reasonable to assume that the animal was restrained, probably by binding the jaws and immobilizing the head and tail (Davis, 2016). The wound’s location and morphology indicate that it was inflicted by a right-handed individual standing to the animal’s left side, wielding a double-edged dagger approximately 30–35 cm in length, which is consistent with known ancient Egyptian ritual weapons such as Tutankhamun’s dagger (Comelli et al., 2016). The lack of repeated blows suggests that the strike was delivered by a practiced hand, possibly a priest, as part of ritualistic killing.

This killing method likely reflects a practice spanning from roughly 2000 to 50 BC, potentially driven by demand exceeding the natural crocodile availability, given the species’ longevity (Naumov and Kartashev, 1979; Konstantinov and Naumov, 2011). The deliberate concealment of the fatal wound beneath the mummy’s wrappings suggests that this was not public knowledge but rather a secret maintained by priests or initiates. The evidence of deliberate, skilled killing for mummification enriches our understanding of ancient Egyptian ritual practices and crocodile cults, inviting new research into this fascinating aspect of Egypt’s cultural and natural history.

An additional notable feature is the partial absence of skin covering the external mandibular fenestra on the right side of the mandible. The clean edges and the presence of a small skin fragment folded inward suggest intentional trimming while the skin was still fresh, possibly related to mummification practices (Senapati, 2020). Whether this was functional or ritualistic remains unclear and warrants further investigation. Identifying similar patterns in other specimens could shed light on crocodile mummification techniques.

Our morphometric analysis focused on the external mandibular fenestra as a potential diagnostic feature distinguishing Crocodylus suchus (West African crocodile) from Crocodylus niloticus (Nile crocodile). Relevant literature and over 100 publicly available skull images showcased that C. suchus tends to have a more regularly elliptical fenestra, while C. niloticus and other crocodilian species typically exhibit one end as being more pointed. This pattern held for juvenile and adult specimens, but exceptions and individual variability were noted.

For the studied mummy, the fenestra ratio aligns most closely with C. suchus morphology, thereby supporting identification as a West African crocodile, consistent with Herodotus’s account that Egyptians distinguished between the species and preferred the less aggressive C. suchus for temple animals. However, a recent study (Porcier et al., 2019) describes a crocodile mummy with a fenestra more typical of C. niloticus, underscoring the complexity of using fenestra morphology alone as a diagnostic trait. Additional investigations utilizing other technologies, such as CT and DNA analyses, would further clarify the species-level identification of the present specimen. If validated, fenestra morphology could provide a simpler, more cost-effective proxy for distinguishing C. suchus from C. niloticus, aiding conservation efforts and historical studies. Given the recent taxonomic distinction between these sympatric species, accurate identification is essential for understanding their historical range and population dynamics (Shirley et al., 2009; Fergusson, 2010; Hekkala et al., 2010; Shaker and El Bably, 2015; Cunningham et al., 2016).

Based on the contextual data and origin of the examined mummified crocodile from the Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra National Preserve (Inv. No. KPL Arh-826), combined with its morphological characteristics, the evidence herein suggests that this specimen was most likely a West African crocodile (Crocodylus suchus). It has been demonstrated that the animal was deliberately killed for the purpose of mummification, with the fatal wound carefully concealed, indicating that such ritual killings may have been more widespread than previously recognized, despite the sacred status of crocodiles in ancient Egypt.

Furthermore, the observed morphological differences in the external mandibular fenestra between the West African crocodile and other species, particularly the Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus), hold promise as a potential morphological marker. This feature could serve as a practical, cost-effective alternative or complement to DNA analysis for distinguishing these closely related species. However, further research with additional specimens and genetic confirmation will be required to validate this method.

The authors sincerely thank Ronny Friedrich, Ph.D., Susanne Lindauer, Ph.D., and the technical team at the Curt-Engelhorn Centre of Archaeometry, Mannheim, for their expert technical support and assistance with sample preparation and measurement. We also thank Johnica Winter, Ph.D., for her valuable help in refining earlier drafts, and Antonio Messina, M.A., Pg. Dip., for his insightful contributions to this research. Supporting information related to this article can be provided upon request.

Yevheniia Yanish: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, visualization, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing.

Dario Piombino-Mascali: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, project administration, supervision, validation, visualization, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing.

Wilfried Rosendahl: formal analysis, investigation, methodology, resources, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing.

Shidong Chen: formal analysis, investigation, methodology, resources, software, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing.

Ester Oras: formal analysis, investigation, methodology, resources, software, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing.

Mykola Tarasenko: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, supervision, visualization, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing.

Fig. S1: Images of crocodile mummies and modern Nile crocodile skulls processed using Paint 3D for measurement of semi-minor axis ratios.

Fig. S2: Photo of the head of the Kyiv crocodile mummy prepared in Paint 3D for morphometric analysis.

Appendix S1: Details of samples used for analysis of the fenestra shape.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Anderson J., Antoine D. 2019. Scanning Sobek. Mummy of the crocodile god. S. Porcier, S. Ikram, S. Pasquali (eds.) Creatures of earth, water and sky. Essays on animals in ancient Egypt and Nubia. Leiden: Sidestone Press, p. 31–37.

Berruyer C., Porcier S. M., Tafforeau P. 2020. Synchrotron “virtual archaeozoology” reveals how ancient Egyptians prepared a decaying crocodile cadaver for mummification. PLoS ONE, 15(2), Article e0229140. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0229140

Bresciani E. 2005. Sobek, lord of the land of the lake. S. Ikram (ed.) Divine creatures: animal mummies in ancient Egypt. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, p. 199–206. https://doi.org/10.5743/cairo/9789774248580.003.0008

Brunner-Traut E. 1980. Krokodil. W. Helck and W. Westendorf (eds.) Lexikon der Ägyptologie. 3. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, p. 791–801.

Buckley S. A., Clark K. A., Evershed R. P. 2004. Complex organic chemical balms of Pharaonic animal mummies. Nature, 431(7006), p. 294–299. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02849

Comelli D., D’Orazio M., Folco L., El-Halwagy M., Frizzi T., Alberti R., Capogrosso V., Elnaggar A., Hassan H., Nevin A., Porcelli F., Rashed M. G., Valentini G. 2016. The meteoritic origin of Tutankhamun’s iron dagger blade. Meteoritics & Planetary Science, 51(7), p. 1301–1309.

Cunningham S. W., Shirley M. H., Hekkala E. R. 2016. Fine scale patterns of genetic partitioning in the rediscovered African crocodile, Crocodylus suchus (Saint-Hilaire 1807). Peer J, 4, Article e1901. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.1901

Davis B. 2016, December 22. Crocodiles in Vietnam skinned alive in service of fashion. Forbes. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/davisbrett/2016/12/22/crocodiles-in-vietnam-skinned-alive-in-service-of-fashion/?sh=63b390692817

De Cupere B., Van Neer W., Barba Colmenero V., Jiménez Serrano A. 2023. Newly discovered crocodile mummies of variable quality from an undisturbed tomb at Qubbat al-Hawā (Aswan, Egypt). PLoS ONE, 18(1), Article e0279137. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0279137

Ernst M. 1947. Sistematika i proiskhozhdeniye vidov. Gos. izd-vo Inostrannoy literatury: Moscow.

Evershed R. P., Jerman K., Eglinton G. 1985. Pine wood origin for pitch from the Mary Rose. Nature, 314, p. 528–530. https://doi.org/10.1038/314528a0

Evershed R. P., Heron C., Goad L. J. 1990. Analysis of organic residues of archaeological origin by high-temperature gas chromatography and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Analyst, 115(10), p. 1339–1342. https://doi.org/10.1039/AN9901501339

Evershed R. P., Dudd S. N., Copley M. S., Berstan R., Stott A. W., Mottram H., Buckley S. A., Crossman Z. 2002. Chemistry of archaeological animal fats. Accounts of Chemical Research, 35(8), p. 660–668. https://doi.org/10.1021/ar000200f

Fergusson R. A. 2010. Nile crocodile Crocodylus niloticus. S. C. Manolis and C. Stevenson (eds.) Crocodiles status survey and conservation action plan. 3rd edition. Gland: IUCN, p. 84–89.

Fomenko I. A., Shamray H. F. 2006. Yehypets’ki starozhytnosti v kolektsiyi Dnipropetrovs’koho istorychnoho muzeyu im. D.I. Yavornys’koho. Art-pres: Dnipropetrovs’k.

Frankfurter D. 1998. Religion in Roman Egypt: assimilation and resistance. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Gałczyńska C. Z. 2015. Aleksander Branicki (1821-1877). Pierwszy Polski archeolog-amator nad Nilem. Materiały Archeologiczne, 40, p. 271–298.

Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire E. 1807. Description de deux crocodiles qui existent dans le Nil, comparés au crocodile de Saint-Domingue. Annales du Muséum d’histoire naturelle, 10, p. 67–86.

Hekkala E. R., Amato G., Desalle R., Blum M. J. 2010. Molecular assessment of population differentiation and individual assignment potential of Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus) populations. Conservation Genetics, 11, p. 1435–1443. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10592-009-9970-5

Hekkala E. R., Shirley M., Amato G., Austin J., Charter S., Thorbjanarson J., Vliet K., Houck M., Desalle R., Blum M. 2011. An ancient icon reveals new mysteries: mummy DNA resurrects a cryptic species within the Nile crocodile. Molecular Ecology, 20(20), p. 4199–4215. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05245.x

Hekkala E. R., Colten R., Cunningham S. W., Smith O., Ikram S. 2022. Using mitogenomes to explore the social and ecological contexts of crocodile mummification in ancient Egypt. Bulletin of the Peabody Museum of Natural History, 63(1), p. 3–14. https://doi.org/10.3374/014.063.0101

Hopfner T. 1913. Der Tierkult der alten Ägypter nach dem Grieshisch-Römischen Berichten und den wichtigeren Denkmälern. Wien: In Kommission bei Alfred Hölder.

Hutton J. M. 1987. Morphometrics and field estimation of the size of the Nile Crocodile. African Journal of Ecology, 25(4), p. 225–230. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2028.1987.tb01113.x

Ikram S. 2010. Crocodiles: guardians of the gateways. Z. Hawass and S. Ikram (eds.) Thebes and beyond: studies in honour of Kent R. Weeks. SCA: Cairo, p. 85–98.

Kákosy L. 1980. Krokodilkult. W. Helck and W. Westendorf (eds.) Lexikon der Ägyptologie. 3. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, p. 801–811.

Keaveney E. M., Reimer P. J., 2012. Understanding the variability in freshwater radiocarbon reservoir offsets: a cautionary tale. Journal of Archaeological Science, 39(5), p. 1306–1316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2011.12.025

Kockelmann H. 2017. Der Herr der Seen, Sümpfe und Flußläufe. Untersuchungen zum Gott Sobek und den ägyptischen Krokodilgötter-Kulten von den Anfängen bis zur Römerzeit. 1-3. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag (Ägyptologische Abhandlungen, 74).

Konstantinov V. M., Naumov S. P. 2011. Zoologia pozvonochnyh. Academia: Moscow.

Kromer B., Lindauer S., Synal H.-A., Wacker L. 2013. MAMS – a new AMS facility at the Curt-Engelhorn-Centre for Archaeometry, Mannheim, Germany. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research B: Beam Interactions with Materials and Atoms, 294, p. 11–13.

Lanting J. N., van der Plicht J. 1998. Reservoir effects and apparent 14C-ages. The Journal of Irish Archaeology, 9, p. 151–165. https://www.jstor.org/stable/30001698

McKnight L. M., Bibb R., Cooper F. 2024. Seeing is believing – the application of three-dimensional modelling technologies to reconstruct the final hours in the life of an ancient Egyptian crocodile. Digital Applications in Archaeology and Cultural Heritage, 34, Article e00356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.daach.2024.e00356

Ménager M., Azémard C., Vieillescazes C. 2014. Study of Egyptian mummification balms by FT-IR spectroscopy and GC-MS. Microchemical Journal, 114, p. 32–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.microc.2013.11.018

Naumov N. P., Kartashev N. N. 1979. Zoologia pozvonochnyh. Part 2. Academia: Moscow.

Nestler J. H. 2012. A geometric morphometric analysis of Crocodylus niloticus: evidence for a cryptic species complex (Masterʼs thesis, University of Iowa). Iowa City: Iowa, USA. https://doi.org/10.17077/etd.tyxbmpzr

Nicolotti M., Robert L. 1994. Les cocodriles momifiés du museum de Lyon. Nouvelles archives du Muséum d’histoire naturelle de Lyon, 32, p. 4–62.

Oaks J. R. 2011. A time-calibrated species tree of Crocodylia reveals a recent radiation of the true Crocodiles. Evolution, 65(11), p. 3285–3297. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01373.x

Oras E., Anderson J., Tõrv M., Vahur S., Rammo R., Remmer S., Mölder M., Malve M., Saag L., Saage R., Teearu-Ojakäär A., Peets P., Tambets K., Metspalu M., Lees D. C., Barclay M. V. L., Hall M. J. R., Ikram S., Piombino-Mascali D. 2020. Multidisciplinary investigation of two Egyptian child mummies curated at the University of Tartu Art Museum, Estonia (Late/Graeco-Roman Periods). PLoS ONE, 15(1), Article e0227446. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0227446

Piombino-Mascali D., Jankauskas R., Piličiauskienė G., Girčius R., Ikram S., Caliò L. M., Messina A. 2023. Crocodile rock! A bioarchaeological study of ancient Egyptian reptile remains from the National Museum of Lithuania. Archaeologia Lituana, 24, p. 115–123. https://doi.org/10.15388/ArchLit.2023.24.7

Porcier S., Berruyer C., Pasquali S., Ikram S., Berthet B., Tafforeau P. 2019. Wild crocodiles hunted to make mummies in Roman Egypt: evidence from synchrotron imaging. Journal of Archaeological Science, 110, p. 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2019.105009

Quirke S. 2013. Going out in daylight – prt m hrw: the ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead: translation, sources, meanings. London: Golden House Publications (GHP Egyptology, 20).

Reimer P. J., Austin W. E. N., Bard E., Bayliss A., Blackwell P. G., Ramsey C. B., Butzin M., Cheng H., Edwards R. L., Friedrich M., Grootes P. M., Guilderson T. P., Hajdas I., Heaton T. J., Hogg A. G., Hughen K. A., Kromer B., Manning S. W., Muscheler R., Palmer J. G., Pearson C., van der Plicht J., Reimer R. W., Richards D. A., Scott E. M., Southon J. R., Turney C. S. M., Wacker L., Adolphi F., Büntgen U., Capano M., Fahrni S. M., Fogtmann-Schulz A., Friedrich R., Köhler P., Kudsk S., Miyake F., Olsen J., Reinig F., Sakamoto M., Sookdeo A., Talamo S. 2020. The IntCal20 Northern Hemisphere radiocarbon age calibration curve (0-55 cal kBP). Radiocarbon, 62(4), p. 725–757. https://doi.org/10.1017/RDC.2020.41

Richardin P., Porcier S., Ikram S., Louarn G., Berthet D. 2017. Cats, crocodiles, cattle, and more: initial steps toward establishing a chronology of ancient Egyptian animal mummies. Radiocarbon, 59(2), p. 595–607. https://doi.org/10.1017/RDC.2016.102

Rosendahl W., Döppes D. 2015. The radiocarbon method - basic principles and applications. B. Madea (ed.) The estimation of the time since death. 3rd edition. Taylor & Francis Ltd: New York, p. 259–265.

Senapati A. 2020, July 3. Villagers in Odisha’s Malkangiri kill, consume meat of mugger crocodile. Down to Earth. Available at: https://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/environment/villagers-in-odisha-s-malkangiri-kill-consume-meat-of-mugger-crocodile-72108

Schmitz A., Mansfeld Р., Hekkala Е., Shine Т., Nickel N., Amato G., Böhme W. 2003. Molecular evidence for species level divergence in African Nile crocodiles Crocodylus niloticus (Laurenti, 1786). Comptes Rendus Palevol, 2(8), p. 703–712. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crpv.2003.07.002

Shaker N. A., El-Bably S. H. 2015. Morphological and radiological studies on the skull of the Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus). International Journal of Anatomy and Research, 3(3), p. 1331–1340. http://dx.doi.org/10.16965/ijar.2015.206

Shirley M. H., Oduro W., Beibro H. Y. 2009. Conservation status of crocodiles in Ghana and Côte-d’Ivoire, West Africa. Oryx, 43(1), p. 136–145. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0030605309001586

Shirley M., Villanova V., Vliet K., Austin J. 2015. Genetic barcoding facilitates captive and wild management of three cryptic African crocodile species complexes. Animal Conservation, 18(4), p. 322–330. https://doi.org/10.1111/acv.12176

Tarasenko M. O. 2019. U poshukakh starozhytnostey z daru khedyva. Davn’oyehypets’ki pam’yatnyky XXI dynastiyi v muzeyakh Ukrayiny. Kyiv: Instytut skhodoznavstva im. A. Yu. Kryms’koho NAN Ukrayiny.

Tarasenko M. O. 2021. Egyptian mummies in Ukrainian museums: an overview. Journal of the Hellenic Institute of Egyptology, 4, p. 145–150. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5775564

Tchapla A., Méjanelle P., Bleton J., Goursaud S. 2004. Characterisation of embalming materials of a mummy of the Ptolemaic era. Comparison with balms from mummies of different eras. Journal of Separation Science, 27(3), p. 217–234. https://doi.org/10.1002/jssc.200301607

Turayev B. A. 1899. Opisaniye egipetskikh pamyatnikov v russkikh muzeyakh i sobraniyakh, Ch. V–VI. Zapiski Vostochnogo otdeleniya Imp. Russkogo arkheologicheskogo obshchestva, 12, p. 191–217.

Verdade L. M. 1997. Morphometric analysis of the broad–snout caiman (Caiman latirostris): an assessment of individual’s clutch, body size, sex, age, and area of origin (Doctoral dissertation, University of Florida). Gainesville: Florida, USA. http://ufdc.ufl.edu/AA00039828/00001

Wasef S., Wood R., El Merghani S., Ikram S., Curtis C., Holland B., Willerslev E., Millar C. D., Lambert D. M. 2015. Radiocarbon dating of sacred ibis mummies from ancient Egypt. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports, 4, p. 355–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2015.09.020

Warner J. K., Combrink Х., Calverley Р., Champion G., Downs C. T. 2016. Morphometrics, sex ratio, sexual size dimorphism, biomass, and population size of the Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus) at its southern range limit in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Zoomorphology, 135, p. 511–521. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00435-016-0325-8

Wu X. B., Xue H., Wu L. S., Zhu J. L., Wang R. P. 2006. Regression analysis between body and head measurements of Chinese alligators (Alligator sinensis) in captive population. Animal Biodiversity and Conservation, 29(1), p. 65–71. https://doi.org/10.32800/abc.2006.29.0065

Yevheniia Yanish, Dario Piombino-Mascali, Wilfried Rosendahl, Shidong Chen, Ester Oras, Mykola Tarasenko

Santrauka

Šiame tyrime nagrinėjamas retas mumifikuoto krokodilo pavyzdys iš Kijevo Pečorų lauros nacionalinio draustinio Ukrainoje kolekcijos, manoma, kilęs iš senovės Egipto. Krokodilo mumija, remiantis radiokarboniniais tyrimais, datuojama I tūkstantmečio viduriu–pabaiga, suteikia vertingos informacijos apie senovės egiptiečių krokodilų mumifikavimo praktikas ir rūšių identifikavimo metodus. Tradiciškai krokodilai buvo laikomi šventaisiais gyvūnais, susijusiais su dievu Sobeku, ir dažnai buvo manoma, kad mumifikuoti krokodilai mirė natūralia mirtimi arba buvo sugauti gyvi ritualiniais tikslais. Tačiau šis tyrimas atskleidžia, kad krokodilas buvo tyčia nužudytas mumifikavimui, kaip liudija paslėpta kaklo žaizda, padaryta duriamuoju-pjaunamuoju ginklu, kuri buvo užmaskuota tvarsčiu, o tai rodo, kad ritualinio žudymo praktika buvo sudėtingesnė ir plačiau paplitusi nei buvo manoma anksčiau.

Morfometrinė tiriamojo egzemplioriaus kaukolės, ypač išorinio apatinio žandikaulio langelio formos, analizė parodė, kad krokodilas priklauso Vakarų Afrikos krokodilo rūšiai, o ne, kaip dažniau manoma, Nilo krokodilo rūšiai. Šis skirtumas turi svarbią reikšmę siekiant suprasti geografines ir kultūrines krokodilo mumifikavimo tradicijas ir rodo, kad langelio morfologija gali būti patikima alternatyva DNR analizei, siekiant atskirti rūšis archeologiniuose pavyzdžiuose.

Šie atradimai paneigia ankstesnes prielaidas dėl krokodilų naudojimo senovės ritualuose ir praplečia žinias apie senovės žmonių ir gyvūnų santykius. Įrodydama tyčinį žudymą ir specifines mumifikavimo technikas, studija pabrėžia ritualinę krokodilų reikšmę, kuri pranoksta jų šventą statusą. Be to, šis darbas pabrėžia archeometrinio datavimo, morfologinių tyrimų ir išsamaus muziejų kolekcijų tyrimo integravimo vertę siekiant atskleisti paslėptą istoriją. Apskritai, tyrimas pateikia naują požiūrį į krokodilų mumifikavimą, rūšių identifikavimą ir senovės Egipto ritualines praktikas, sudarydamas pagrindą tolesniems tarpdisciplininiams tyrimams archeologijos ir zoologijos srityse.